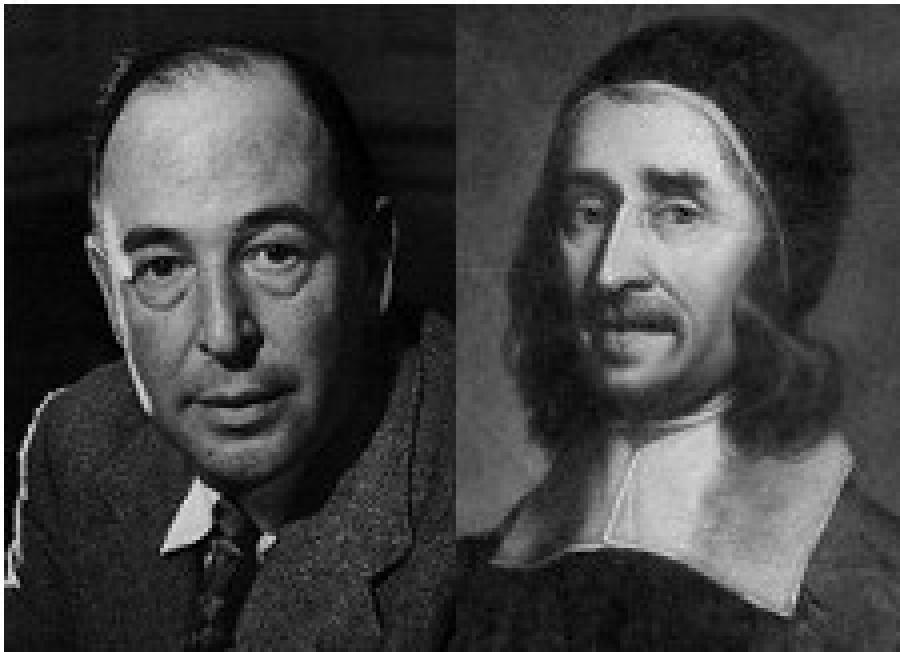

Mere Christianity: An Examination of the Concept in Richard Baxter & C. S. Lewis (Part 2)

Image

From Detroit Baptist Seminary Journal (DBSJ), with permission. This section continues to examine Baxer’s concept of mere Christianity. Read Part 1.

Baxter’s Non-Denominational Stance

The source of Baxter’s anti-denominational stance is explained by multiple factors. A major factor was grounded in Baxter’s belief that all worship is faulty. The Presbyterian will criticize the Anglican mode of worship, and the Anglican will respond in like manner. But Baxter believed that neither had the higher ground. He arrived at this conclusion by consideration of human depravity. That is, since every aspect of man’s life is fallen, even the best worship will be marred. Thus Baxter says,

For while all the worshippers are faulty and imperfect, all their worship will be too: and if your actual sin, when you pray or preach effectively yourselves, doth not signify that you approve your faultiness; much less will your presence prove that you allow of the faultiness of others. The business that you come upon is to join with a Christian congregation in the use of those ordinances which God hath appointed, supposing that the ministers and worshippers will all be sinfully defective, in method, order, words, or circumstances: and to bear with that which God doth bear with, and not to refuse that which is God’s for the adherent faults of men, no more than you will refuse every dish of meat which is unhandsomely cooked, as long as there is no poison in it, and you prefer it not before better.1

In another, similar, context Baxter said, “All our worship of God is sinfully imperfect, and that it is a dividing principle to hold, that we may join with none that worship God in a faulty manner; for then we must join in the worship of none on earth.”2 For Baxter, error cannot be avoided while on earth. One who seeks to worship in perfection can worship with no one—not even himself! Consequently, if we accept faults in our own worship, we should accept the faults in our brothers’ worship as well.3

Though Baxter does not explicitly note politics as a source of his anti-denominationalism, his historical circumstances forced him to think critically about the role of politics in religion. Whatever political position was in power attempted to force its religious views on the country. If his vision of anti-denominationalism succeeded, there would be no coercion and persecution. In Baxter’s view, Christianity supersedes political lines and should not be drawn alongside of them.

Baxter’s anti-denominational stance can be attributed to another factor—the sinfulness of division. Baxter defines a Christian as one who

is an esteemer of the unity of the church, and is greatly averse to all divisions among believers. As there is in the natural body an abhorring of dismembering or separating any part from the whole; so there is in the mystical body of Christ. The members that have life, cannot but feel the smart of any distempering attempt: for abscission is destruction…. He looketh at uncharitableness, and divisions, with more abhorrence than weak Christians do at drunkenness or whoredom, or such other heinous sin…. Therefore he is so far from being a divider himself, that when he seeth any one making divisions among Christians, he looketh on him as on one that is mangling the body of his dearest friend, or as one that is setting fire on his house, and therefore doth all that he can to quench it; as knowing the confusion and calamity to which it tendeth.4

His justification for such strong language is grounded in his understanding of the following Scriptures: Romans 16:17–18; Acts 20:29–30; and Philippians 2:1–3. Division, he argued, was against God’s will, disrupting the unity of the church. His picturesque analogies (dismembering, mangled bodies, and house on fire) display the abhorrence Baxter felt for division in the church. Paul’s analogy of the body of Christ was more than a mere picture; it described a spiritual reality. Thus, he believed the conscientious Christian must also abhor disunity and denominational factions. The only recourse was to reconstitute the whole, creating a unified, functioning body once more.

A final reason Baxter embraced anti-denominationalism concerns its role in Christian apologetics. Baxter believed that the gospel of Christ was hindered by division. Speaking of his own ministry, Baxter stated, “When people saw diversity of Sects and Churches in any place, it greatly hindered their conversion…. But they had no such offence of objection [at Kidderminster]…for we were all but as one.”5 Baxter labored hard to eliminate sectarian divisions among Christians at Kidderminster, and he was quite effective, for he was able to say later that “I know not of an Anabaptist, or Socinian, or Arminian, or Quaker, or Separatist, or any such sect in the town where I live; except a half dozen Papists that never heard me.”6 His success in erasing the divisions between Christians, he believed, led the way to apologetic success. A fully unified army of believers presenting the gospel to the world was much more effective than each sectarian group making individual advancements.

Baxter’s Conception of a Mere Christian

On the negative side, we have examined the core reasons Baxter held to anti-denominationalism, but on the positive side, it would be helpful here to delineate precisely what Baxter meant by MC. That is, who is included as a Mere Christian and why is he included? Baxter gives five requirements for being a Mere Christian.7 First, one must hold to those beliefs that are evident from the apostolic times. In this way, Baxter was not disavowing the role of church history in doctrinal formation. He believed that the modern church must seek to live out the true tradition passed on by the apostles. More specifically, Baxter believed the content of apostolic teaching, church history, and the common interpretations of the present church presented the following core truths:

The Christian faith is “the believing an everlasting life of happiness to be offered by God (with the pardon of all sin) as procured by the sufferings and merits of Jesus Christ, to all that are sanctified by the Holy Ghost, and do persevere in love to God and to each other, and in a holy and heavenly conversation.” This is saving faith and Christianity, if we consent as well as assent.8

Second, true Christians must adhere to teaching that is “plainly and certainly expressed in the Holy Scripture.”9 The two adjectives are extremely important. The beliefs received from the Scripture must not be unique to each reader. The Scripture is perspicuous, yet there are many things that remain enigmatic, and to those issues man should not become divisive. Opinions may be given and held, but they should not become a standard of orthodoxy or communion. For this reason, Baxter was opposed to detailed creeds, for when they focused on more than the essentials they could tend to “multiply controversies, and fill the minds of men with scruples, and ensnare their consciences, and engage men in parties against each other to the breach of Christian charity.”10 Creeds, in Baxter’s mind, sought to go beyond Scripture to establish with certainty what Scripture had not clearly revealed. The end result, at least in Baxter’s mind, was division and sectarianism.

The third characteristic, which is a further implication of the first, is that Mere Christians agree to doctrine that has been held by the universal church throughout the ages.11 True Christianity, Baxter argued, would be grounded in the Bible and would follow the traditions laid down by Christ and the apostles. Consequently, the Mere Christian must find himself in continuity with the line of true Christians throughout the centuries. Historical continuity with believers of past ages served as both a proof of identity as well as a sign of God amongst his people.

Harmony of essential belief among a modern community of faith is the fourth characteristic of Mere Christians. The problem with this characteristic concerns its circularity; that is, one cannot define a Mere Christian by referring to Mere Christians. Thus, the scope of this characteristic is necessarily limited. However, one can see that Baxter was seeking to express the impressive unity amongst believers cultivated by those who seek to honor Scripture first. As far as they are successful, they will become attractive to other true believers. In this way, they will give credibility to their own interpretation of Scripture. Summarizing the previous points, one finds that the Mere Christian is one who follows in the footsteps of the apostles, follows the Scripture in all things, gauges his interpretations of Scripture by the interpretations of church history, and gauges his interpretation by modern interpreters who are likewise devoted to sola scriptura.

The final characteristic of a Mere Christian concerns the fruit of conversion. Baxter stated the truth this way: “Every man in the former ages of the church was admitted to this catholic church communion, who in the baptismal vow or covenant gave up himself to God, the Father, Son and Holy Ghost, as his Creator, Redeemer and Sanctifier, his Owner, Governor and Father, renouncing the flesh, the world and the devil.”12 Baxter believed a true change must accompany the conversion of a Mere Christian. Mental assent to the aforementioned truths was not enough. The path of membership travelled to the cross of Christ where the pride of man is stripped away and the work of God is permanently started in the heart of the believer.

Before leaving Baxter’s requirements of a Mere Christian, it is fruitful to also examine what Baxter taught about extraneous beliefs. What should one do about beliefs that were beyond the scope of MC—e.g., whether one should use extemporaneous or liturgical prayers? Neither method of prayer is clearly taught in Scripture, so is one to suspend belief on the question? Baxter believed in what we will call undiluting addition. According to this position, one could be a Mere Christian while holding many things that were not necessarily clear in Scripture. More strikingly, Baxter held that one could be a Mere Christian while holding to a whole plethora of beliefs that were not true. Keeble summarized the position by noting that Baxter had a “readiness to welcome as true Christians any who held these essentials no matter what further beliefs they also maintained.”13 Baxter noted of himself, “I confess I affect none of the honour of that orthodoxness, which consisteth in sentencing millions and kingdoms to hell, whom I am unacquainted with.”14 He wanted to judge those outside by only the essentials and not by the beliefs he added to the essential truths of the gospel.

Of course, Baxter did not believe every extra belief attached to Christianity was acceptable. Some extra beliefs dilute the essential beliefs and ultimately cause one to modify the essential belief. When this happens, the external belief has invalidated the essential belief, and the person indicated cannot properly be called a Mere Christian. As an example, Baxter cited the beliefs of the Catholic Church:

If Papists, or any others, corrupt this religion with human additions and innovations, the great danger of these corruptions is, lest they draw them from the sound belief and serious practice of that ancient Christianity which we are all agreed in: and (among the Papists, or any other sect) where their corruptions do not thus corrupt their faith and practice in the true essentials, it is certain that those corruptions shall not damn them.15

In summary, if a belief brings the essentials into question, then the proponents cannot properly be called a Mere Christian. If however, the extra beliefs do not bring the essentials into question, he may be wrong, but he is still a Mere Christian.

Notes

1 Richard Baxter, The Practical Works of Richard Baxter (London: Paternoster Row, 1830), 8:358–59.

2 Ibid., 8:470.

3 We should add one caveat: Baxter did not say that a Christian should join any congregation in worship. If the congregation worshipped in a fashion that imposed sin upon the worshipper (e.g., Roman Catholic communion), then it should be avoided (ibid., 4:537).

4 Ibid., 8:468–69, emphasis added.

5 Richard Baxter, Select Practical Writings of Richard Baxter: With a Life of the Author (London: Durrie & Peck, 1831), 1:115.

6 Baxter, The Practical Works, 16:393.

7 West, “Richard Baxter and the Origin of ‘Mere Christianity.’”

8 Baxter, The Practical Works, 7:475.

9 Ibid., 8:476.

10 Ibid., 16:491.

11 Ibid., 8:476.

12 Ibid.

13 Keeble, “C. S. Lewis, Richard Baxter,” 32.

14 As cited ibid.

15 Baxter, The Practical Works, 7:476.

Tim Miller Bio

Dr. Tim Miller is Assistant Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary. He received his M.A. from Maranatha Baptist University, his M.Div. from Calvary Baptist Theological Seminary, and his Ph.D. in historical theology from Westminster Theological Seminary.

- 21 views

Here is the quotation you gave of Baxter’s conception of a Mere Christian:

The Christian faith is “the believing an everlasting life of happiness to be offered by God (with the pardon of all sin) as procured by the sufferings and merits of Jesus Christ, to all that are sanctified by the Holy Ghost, and do persevere in love to God and to each other, and in a holy and heavenly conversation.” This is saving faith and Christianity, if we consent as well as assent.

It seems to me that you cannot be a Mere Christian if you want to study your Bible. For example, just from the excerpt above, you’ll have to eventually define:

- What the content of this belief is

- Who defines what “everlasting happiness” is?

- What, then, even is everlasting happiness?

- Who God is

- What sin is

- How can sin be pardoned?

- What does it mean to pardon sin?

- What are sufferings of Christ?

- What are the merits of Christ?

- How did Christ “procure” the everlasting happiness of His children?

- Who did Christ procure this “everlasting happiness” for?

- Who exactly is Christ?

- Who is the Holy Ghost?

- How does the Holy Ghost “sanctify” us?

- What, exactly, does it mean to be sanctified?

- What, exactly, is perseverance?

- What does it mean to persevere in love to other Christians? To God?

- What are the implications if you do not persevere?

- What, exactly, is a “holy and heavenly conversation?”

- What happens is somebody’s “conversation” is not holy and heavenly?

- What is saving faith?

You cannot answer these questions and remain a Mere Christian.. Baxter mentioned Socinians earlier in your article. This alone boggles the mind. We’re talking about two different Messiah’s!

Tyler is a pastor in Olympia, WA and works in State government.

Discussion